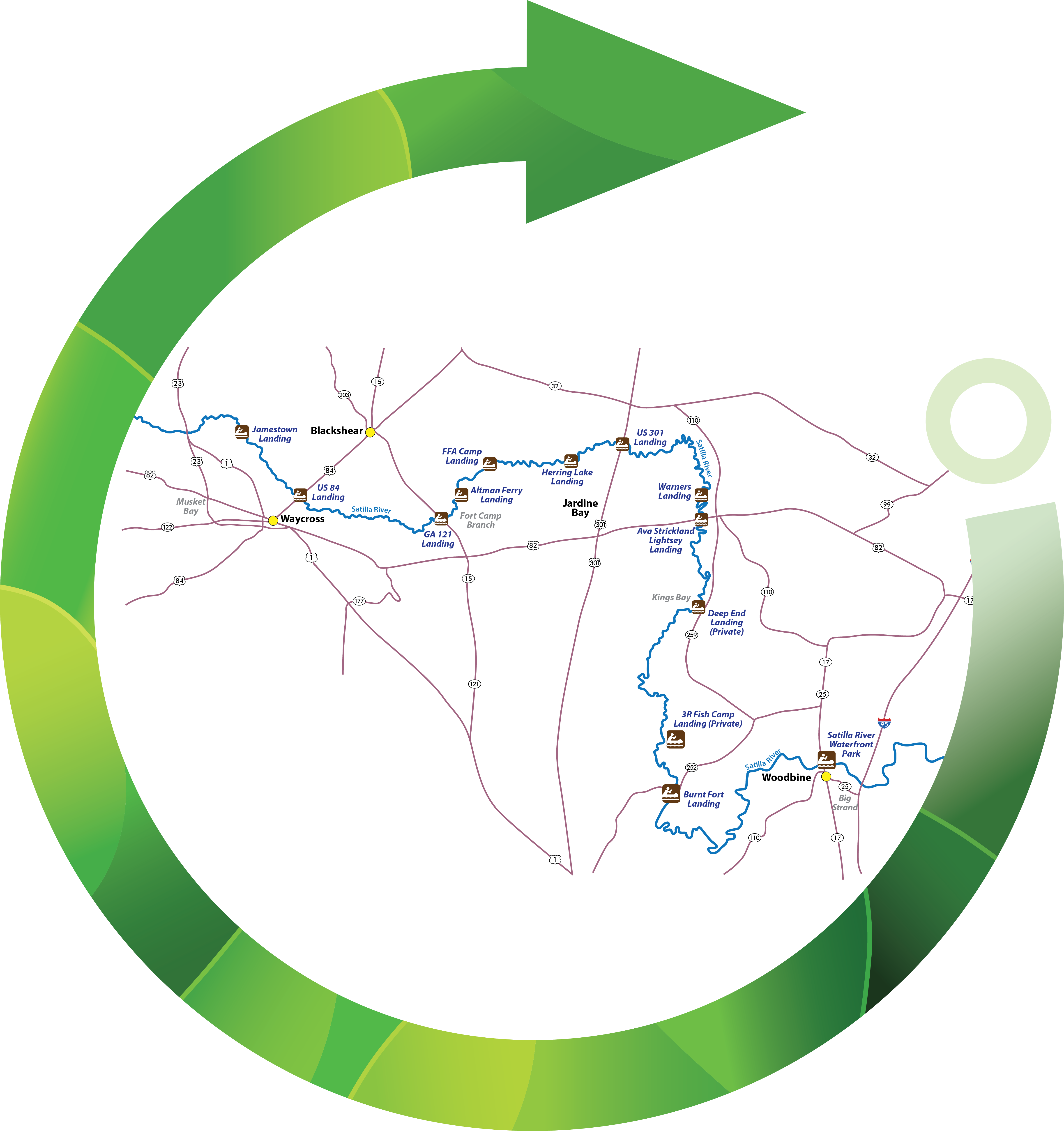

The sandy shores of the Satilla River have been inviting Georgia residents since the area was settled in the early 19th century. Emanating in Ben Hill County near Fitzgerald, the freshwater river touches nine Georgia counties before reaching the tidal marshes separating Glynn and Camden counties along the coast.

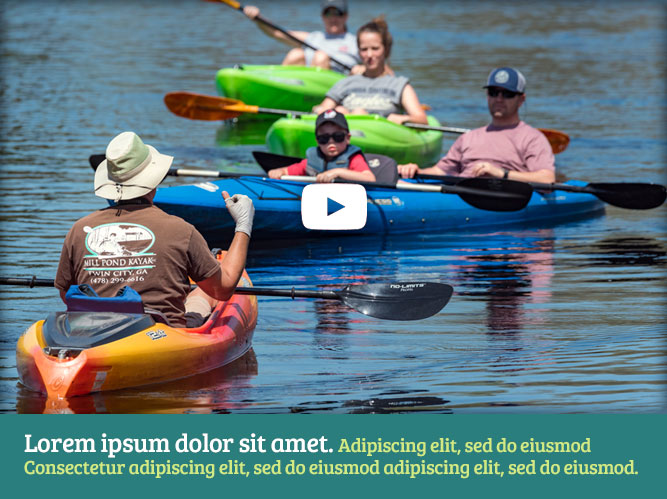

Coursing through South Georgia for more than 200 miles, the Satilla River is largely unencumbered by civilization. River houses dot the banks in certain sections, but most of the land along the waterway is undeveloped, providing a quiet and peaceful paddle filled with the sights and sounds of nature.

Once you slide away from practically any landing along the Satilla, the first thing you notice is the quiet. The sounds of civilization give way to the cacophony of bird that roost and nest in this flourishing avian ecosystem. Chirps, tweets, and screeches fill the air as smaller birds, like swallows, dash just above the water, snagging insects along the way. Barred owls scan for prey perched atop branches, while red-tailed hawks and kite can be seen patrolling the area from the skies above.

Mammals who call the riverside home include deer, hogs, and beaver. Alligators are spotted from time to time but seeing their tracks is the more common occurrence. Several species of snakes rest on the forested banks, while redbreast sunfish, redear sunfish, bluegill, largemouth bass and catfish enjoy the confines of the blackwater.

Although it rarely falls below 5 feet, there are times when the waterway is only navigable by kayak or canoe. During times of higher water levels, johnboats and small watercraft are common as well. Before you paddle, it’s recommended that you check the Satilla Riverkeeper’s website which provides updates on water levels and navigability through a series of gauges on the river.

While the average flow of the river is around 700 cubic feet per second (CFS), the river toggles between 30 CFS and 16,000 CFS throughout the year. The Satilla’s flow rate is tied directly to water level, which fluctuates by season, ranging from 2 to 5 feet deep in the dry summer and upwards of 15 feet in the rainy fall and winter.

It’s nearly impossible to get through a paddle without at least a little bit of a workout. Even if you’re traveling with the current, it typically isn’t strong enough to push you the entire way. More paddling would be required if time or distance is a factor.

Tidal currents only come into play at 3 R Fish Camp in Camden County and points east along the river toward the Atlantic. Paddlers should be aware of the tides.

Recommended Paddle: GA-121 Landing to Altman Ferry Landing, Loop

As the meandering blackwater follows the path of least resistance on its way to the Atlantic Ocean, it passes along the southern edge of Pierce County, which boasts some of the most peaceful and picturesque sections of the river. The GA-121 Landing is on the north side of the Satilla, which serves as the Pierce County border with neighboring Brantley County. The GA-121 Landing is one of the county’s two main entries and is arguably the most popular in the area.

Heading west from the GA-121 Landing at the southern border of Pierce County, the rumbling of the two-lane overpass fades quickly. In short order, paddlers are fully immersed in a forest of cypress and skinny pines which provide dappled shade from the warming sun.

In times of lower water, navigating west from GA-121 Landing may be short-lived. Higher water periods, like winter and spring, will allow paddlers to meander through the cypress forest down blackwater alleys.

Heading east from the landing, there is no overhanging canopy so the full view of the river and the sandy outcroppings that line the banks are on display. The main obstacles along the waterway typically are fallen trees, knowns as strainers, and of course, the sandbars, which can remain hidden just inches below the surface.

Since the sandy riverbed is playable, meaning the river can be reshaped rather quickly, sandbars will shift from waterflow as sediment collects on the inside edge and oxbow lakes have been known to from time to time, dissipating during times of higher water levels.

Sandbars, however, are integral to the public use of the river, serving often as overnight campsites and daytime hangout spots for paddlers along the journey. Accurately called “sugar sand” for its grainy texture, yet white color, the sand is left over from prehistoric times when Georgia’s lowlands were under the Atlantic Ocean. No Pierce County paddle would be complete without at least one jaunt onto the white mounds.

Overnight camping is permitted on the public sections of the banks and sandbars; however, campers should make sure the water level will not change at the campsite. Water levels can change significantly in a few days in this flashy system.

Parking is permitted at the GA-121 Landing and most paddlers prefer to make round trips back to their load-in spot and parked vehicle. The low flow and limited current make westerly paddles along the easterly flowing river manageable.

A great turnaround spot is Altman Ferry Landing, which sits on the Brantley County side of the Satilla. Just 4 miles downriver, an 8-mile roundtrip is manageable for most paddlers of moderate fitness and experience. If a 10-mile one-way paddle is in your plans, an ideal pickup area would be the FFA Camp Landing. The wide banks and bricked ramp make exiting and loading a breeze.

Distance: 140 mi

Distance: 140 mi

Difficulty: Class 1 and flatwater

Difficulty: Class 1 and flatwater

Directions

Directions

2 months ago

2 months ago